George Mason University, Virginia Tech, and the University of Virginia are each recognized and valued for their unique strengths and assets. Consequently, it’s not surprising to conclude that when these three institutions collaborate on a project, the results are impressive. Such was the case with a recent 4-VA grant to these top-tier universities for a project entitled “ReSounding the Archives” (RtA).

This effort was designed to take full advantage of a distinctive set of circumstances and situations, which combined history, music, and digital humanities with the ability to access music prior to 1924 without copyright restrictions. It all began with Mason’s lead PI Kelly Schrum, Associate Professor in the Higher Education Program at George Mason University and former Director of Educational Projects at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (RRCHNM), who identified the genesis of the project during the 100th anniversary of WWI to bring the newly digitized music of that time period to life. “In this project, each institution was able to contribute an integral element: UVA had access to WWI sheet music in their archives and created a research class around the project; Mason had the performers, digital history education specialists, and website developers; and VT contributed sheet music, research, and performers,” says Schrum.

Schrum recalls the early days of the project, “We drew on our connections with Tech and UVA and everyone we discussed the idea with began to get really excited about bringing historical sheet music to life. It started to develop organically based on each institution’s resources and strengths, but we knew we were onto something good when the energy of the project travelled to all potential contributors, from musicians and archivists to librarians and students.”

Jessica Dauterive, a Mason PhD student in History who worked as a Digital History Fellow at RRCHNM, was intimately involved with the project from beginning to end. Dauterive recounted one of her first interactions with RtA when she emailed Mark Brodsky, Public Services and Reference Archivist at the VT library in response to a post on his blog about WWI sheet music. “I cold emailed him, he didn’t know me at all.” Dauterive explained the project to him. “He was all in, immediately!” says Dauterive.

Growing Collaboration

From there, the collaborators went into overdrive: using the telepresence room technology on each campus, students, staff and faculty were able to work together virtually. The groups met three times via the telepresence rooms, beginning with students (ranging from history majors to medical students) who were researching historical sheet from WWI in a class taught by UVA’s Assistant Professor of Music Elizabeth Ozment. Then, the student performers began to work on their interpretations of each piece of music. “It really grew from there. The students were excited to work together. They were engaged in learning history though music and music through history,” says Schrum. “Students continued to discuss their pieces in small groups through phone calls and emails.”

Both Schrum and Dauterive concede that even though the energy and enthusiasm were high, the devil is in the collaboration details. “Getting everything synched between campuses can be a challenge, and even coordinating within our own large institution takes work,” notes Schrum.

But as the weeks went on, progress was made. Students researched in the archives and worked to contextualize their pieces as the performers  rehearsed and studied the music within its historical context. And similar to good musical composition, RtA worked to a crescendo. For the RtA team, that was a spring evening in Charlottesville when the team of researchers, performers (musicians and singers), videographers and archivists, librarians, faculty and more joined together in UVA’s Colonnade Club Garden Room to fully embrace 17 pieces of WWI music. From “K-K-K Katy” to “Over There” to “Oh How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning” the Colonnade Room sprang to life — circa 1918.

rehearsed and studied the music within its historical context. And similar to good musical composition, RtA worked to a crescendo. For the RtA team, that was a spring evening in Charlottesville when the team of researchers, performers (musicians and singers), videographers and archivists, librarians, faculty and more joined together in UVA’s Colonnade Club Garden Room to fully embrace 17 pieces of WWI music. From “K-K-K Katy” to “Over There” to “Oh How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning” the Colonnade Room sprang to life — circa 1918.

The evening was a success, with contributors and collaborators enjoying the fruits of their labor.

- Elizabeth Ozment, whose class of music researchers at UVA provided the first notes for the project, had this to say, “ReSounding the Archives has built bridges between our institutions. It has brought us together in ways I could never have imagined! This has been incredible for me to see and hear all this wonderful music.”

- Linda Monson, Director of the School of Music at Mason said, “It’s been a delight to be able to bring this music to life. We played a role in 13 of the songs, but this is just the beginning… We are looking forward to continuing to work with UVA and Tech as we move forward on this project. A huge thank you to all who have been part of this.”

- Winston Barham, Music Collections Librarian at UVA, summed it up this way, “This has been one of my greatest delights – to work on a project holistically, from music development to website development.”

- Trudy Becker, Senior Instructor in History at Tech noted, “We all got to do something really exceptional together and we got to immerse ourselves in our special collections library and integrate it into a history lesson.”

And the Beat Goes On

But the project doesn’t end with the researcher’s research and the performer’s performance. Following the musical presentation, the RtA team began composing the second movement. Schrum’s vision was to format the collection in such a way that it would provide a lasting, sustainable digital resource for K- 12 teachers throughout the state to promote teaching history through music. Thus, began the development and production of resoundingthearchives.org.

The website now contains each piece of sheet music featured in the program and includes various entry points for educators, students, and researchers to engage with the sources in a variety of ways: listen to live and studio recordings of each song; view the digitized sheet music; read student essays contextualizing the pieces; and read the transcribed lyrics. Each piece of music is available with full metadata, and all recordings are also available for download, offered under a Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC 4.0), making them available for use in classrooms, digital projects, or even for re-mixing.

Schrum summed up the project’s contributions, “Sheet music is visually interesting, but it really falls short if it’s not heard. Millions of pages of sheet music have been digitized, but if you are not a musician, it’s just dots on a page.”

Already the website is attracting hundreds of visitors monthly, with more than one thousand visiting following a posting about the website by the National WWI Museum and Memorial Facebook page. But both Schrum and Dauterive see much greater things for the website in the future, with Dauterive continuing to make connections and putting guidelines together to allow faculty and teachers to make greater use of the resources. “The website is endlessly extendable,” points out Schrum. They both see an opportunity to expand the project to include Civil War music and political songs.

Extending the Chorus

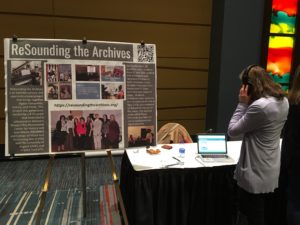

The website also provides the opportunity to bring the resources outside of the Commonwealth to a larger audience. For example, the Deschutes Historical Museum in Bend, Oregon has incorporated RtA resources into a WWI exhibit to accompany sheet music they had on display. Dauterive also made a presentation about the project and the website recently in Hartford, Conn. at the annual meeting of the National Council on Public History which had record attendance of almost 1,000 attendees. Dauterive was able to introduce the project to museum and historic site representatives, national park employees, teachers, and historians and discuss how to share history in an engaging way using music.

Although all the representatives in the collaboration look forward to continued efforts to bring music and history to life, Dauterive is appreciative of the role she’s already played on the project, “I was lucky to be at Mason at this time and have the funding available to play a part in this – I learned how to be a manage a project with so many moving parts and share and expand my knowledge of music history. It was a great opportunity for me personally and professionally.”

Schrum sees the project as an example for the larger 4-VA community, noting “Everyone has 20,000 projects in their head. This 4-VA grant gave us the opportunity to bring this important work to life. We had these great ideas, but the grant provided us the opportunity to collaborate and make it happen. This project is a model of what can be done across institutions and disciplines.”