Annually, one in four senior citizens seek emergency care from a fall-related injury. To help combat this statistic and prevent falls — which are often the result of poor balance — conventional physical therapy rehabilitation approaches have traditionally been utilized. However, many in the physical therapy field now view immersive virtual reality (VR) technology as an intriguing option for older adults. While laboratory-based experiments provide promising findings, to date this technology has yet to be scaled-up and translated into clinical settings.

Two scholars at 4-VA schools with multidisciplinary backgrounds in related fields envisioned a future where clinicians could use affordable VR technology to outperform traditional diagnostics, therapeutics, and pharmaceutical approaches in fall prevention. They saw an opportunity to develop effective uses of VR technology to detect cognitive-motor function in older adults, and identify fall-risk factors for this population.

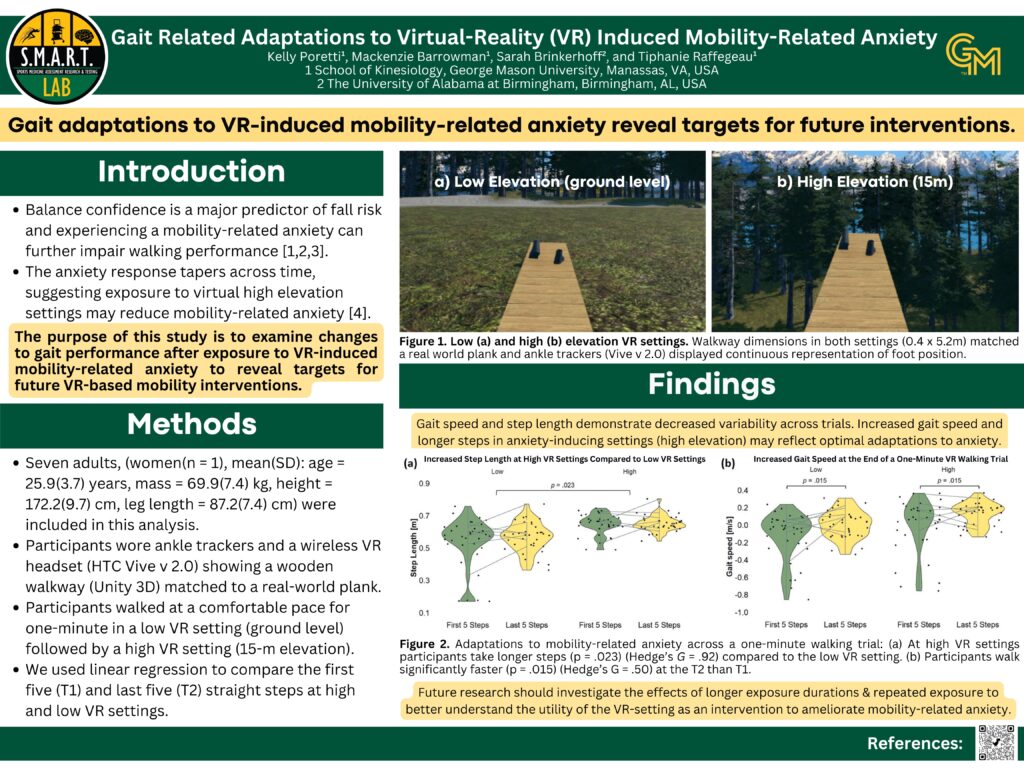

The two scholars, Tiphanie Raffegeau, in George Mason’s School of Kinesiology, College of Education and Human Development, and Christopher Rhea, Old Dominion University’s Associate Dean for Research and Innovation, Ellmer College of Health Sciences, developed this project. Raffegeau’s prior research focused on inducing anxiety during walking to study the fear of falling with an elevated height VR paradigm, while Rhea has primarily concentrated on examining how people adapt their steps to avoid obstacles in virtual environments. Through a 4-VA partnership, they wanted to increase accessibility to rehabilitative VR technology for interventions focused on reducing older adult fall-risk, while developing a framework for future scalable and fundable research.

Following 4-VA approval, Raffegeau hired three student programmers, Trevor Hsu, Chara Canfield, and Micah D Williams from the Virginia Serious Gaming Institute (VGSI), a Mason affiliated entity. The student programmers were supervised by VSGI research faculty member Jacob Enfield.

Raffegeau enlisted two of her graduate students to volunteer on the project — Kelly Poretti and Mackenzie Barrowman.

After a year of research Raffegeau notes, “Our testing proved fruitful and we identified a number of important results.” First, they found that experiencing fall-related anxiety in immersive VR can further impair walking performance. Interestingly, they also found that the anxiety response tapers over time, suggesting that experiencing virtual high elevation settings may reduce fall-related anxiety. They also saw that anxiety-provoking VR settings could promote stability-related adaptations during overground walking in impaired populations, suggesting that the VR experience could serve as a clinical intervention to improve walking.

Their findings were enthusiastically shared at the Gait and Clinical Movement Analysis Society Annual Meeting, the American Society of Biomechanics Annual Meeting, and the College of Education and Human Development Research symposium.

Using preliminary data from the VR project, Poretti was awarded the Switzer Research Fellowship for Doctoral Dissertation Research by the Administration for Community Living for her dissertation project ‘Using Virtual Reality to Reduce Mobility-Related Anxiety in Lower-Limb Prosthetic Users’ which will support her dissertation work. Raffegeau and Rhea recently submitted an NIH R21 proposal to the National Institutes on Aging entitled, ‘Investigating Biobehavioral Responses to Mobility-Specific Anxiety Across the Menopause Transition and the Effects on Mobility and Fall-Risk’ focusing on the effect of VR-induced fall-related anxiety on walking in pre-and post-menopausal older women.

Concludes Raffegeau, “This 4-VA funding provided crucial funds to support my work as an early investigator and it has made my future grant applications stronger as evidence of institutional support for my career trajectory.”

View two videos produced during the research which illustrate the Low VR and High VR findings.

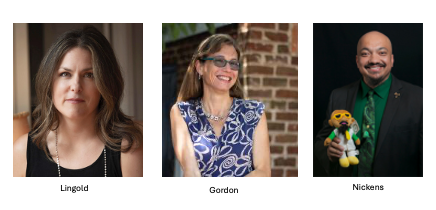

To that end, Green sought the involvement of scholars in the field at several 4-VA partner schools to help her put the project into motion: Mary Caton Lingold at VCU and Bonnie Gordon at UVA. Both readily volunteered their time to bring this multi-level and multi-faceted research to fruition. Michael Nickens (a.k.a. Doc Nix — most recognized as the leader of George Mason University’s “Green Machine,”) also eagerly joined the team. Additionally, Maria Ryan, at Florida State University, came on to collaborate on the project.

To that end, Green sought the involvement of scholars in the field at several 4-VA partner schools to help her put the project into motion: Mary Caton Lingold at VCU and Bonnie Gordon at UVA. Both readily volunteered their time to bring this multi-level and multi-faceted research to fruition. Michael Nickens (a.k.a. Doc Nix — most recognized as the leader of George Mason University’s “Green Machine,”) also eagerly joined the team. Additionally, Maria Ryan, at Florida State University, came on to collaborate on the project.

Today, to Luther’s great delight, the results have proved far more successful than he could have ever anticipated. Tens of thousands of animal images from camera traps and audio recordings have already been collected.

Today, to Luther’s great delight, the results have proved far more successful than he could have ever anticipated. Tens of thousands of animal images from camera traps and audio recordings have already been collected. Hassan, Jordan Seidmeyer, Katie Russell, Carolian Sanabria, Adrian Em, Alix Upchurch, Piper Robinson, Tristan Silva-Montoya, and Estefany Umana spent hours creating this treasure trove of records. Emilia Roberts, a MS student in ESP, managed these undergraduate researchers.

Hassan, Jordan Seidmeyer, Katie Russell, Carolian Sanabria, Adrian Em, Alix Upchurch, Piper Robinson, Tristan Silva-Montoya, and Estefany Umana spent hours creating this treasure trove of records. Emilia Roberts, a MS student in ESP, managed these undergraduate researchers. The project continues to gain traction. The team has created a website featuring the results of the acoustic portion of the research,

The project continues to gain traction. The team has created a website featuring the results of the acoustic portion of the research,

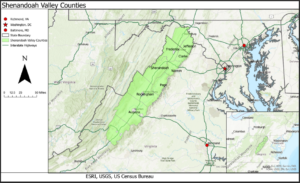

This was achieved following 4-VA’s approval of a proposal by George Mason’s Yun Yu, an Assistant Professor in Chemistry and Biochemistry Department, for a grant entitled

This was achieved following 4-VA’s approval of a proposal by George Mason’s Yun Yu, an Assistant Professor in Chemistry and Biochemistry Department, for a grant entitled